Literature, Modern First Editions

A Low, Dishonest Writer

As a poet, W. H. Auden has always divided opinion. F R Leavis thought his ironic style was ‘horribly show-off’ and ‘morally irresponsible’; while the biographer Hugh McDiarmid referred to the poet as ‘a complete wash-out’. These obituaries might be harsh, but they are a strong contrast to the highly enthusiastic reception of his early verses by luminaries such as Virginia Woolf and T.S. Eliot.

This shift in critical value can be characterised as a divide between the ‘English Auden’, the politically engaged celebrity-writer who masqueraded as a frosty public intellectual, and the ‘American Auden’, the more reserved, eccentric gentleman, whose literary output was exceeded only by his generosity. Such a divide emanates from Auden’s difficult life—his unapologetic homosexuality and notoriously liberal relationship with fellow poet Chester Kallman further blackened his character after his flight to the US in 1939.

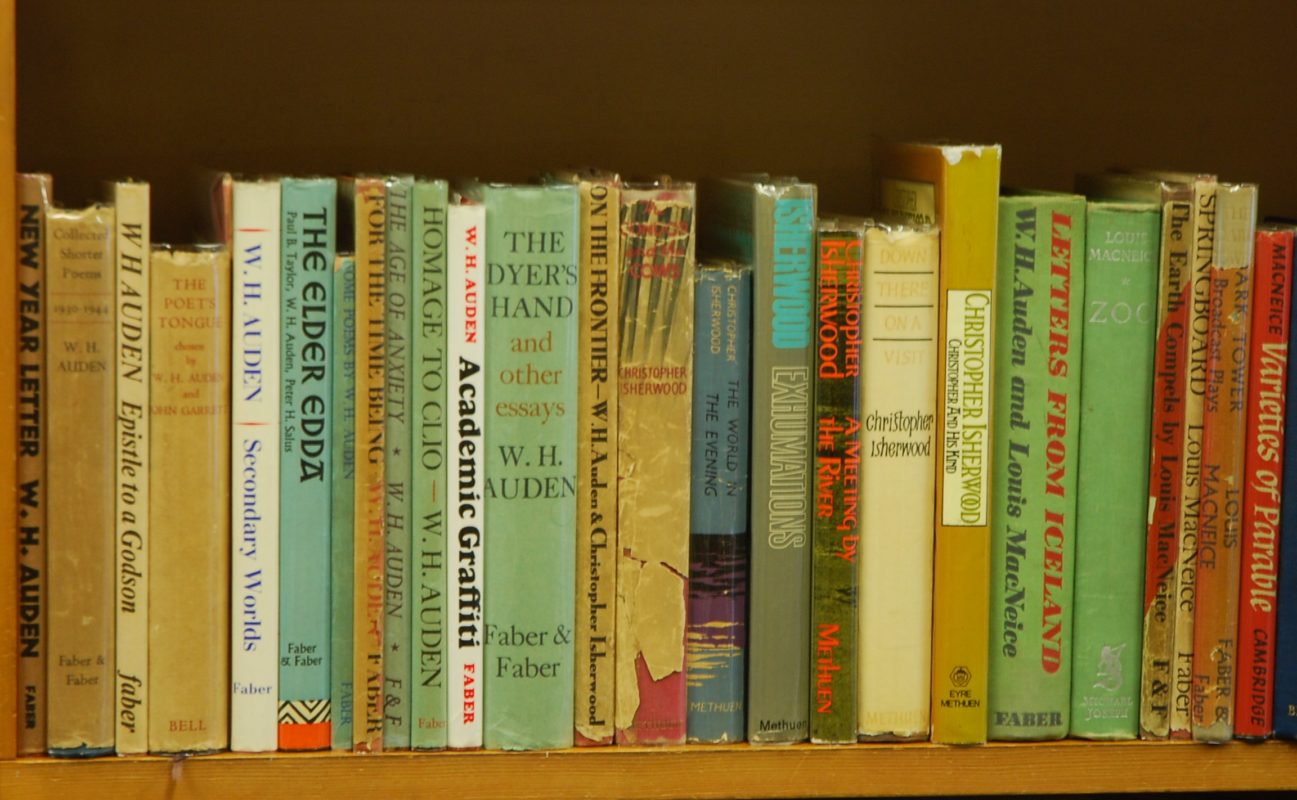

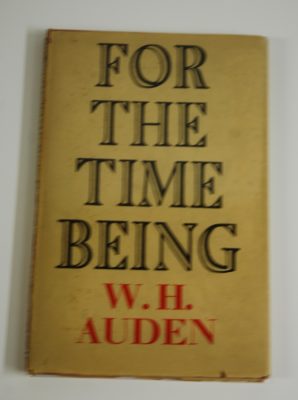

To the conservative British critics, a kind of artistic karma took place: the poet who abandoned his home country at the dawn of war suffered a marked decline in quality. As dramatically appealing as this narrative seems, it simply isn’t true. Soon after settling in New York City, Auden quickly began to produce masterpiece after masterpiece; and it is from this, his most fertile period, that our collection stems.

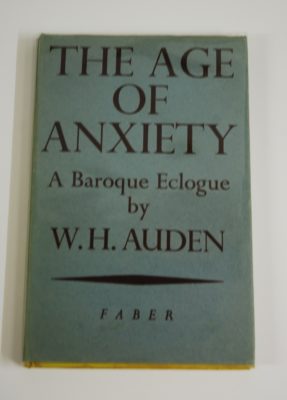

In 1944, Auden began work on The Age of Anxiety, considered by some to be his magnum opus. The regular drinking adventures of four Americans slowly explode, through a series of somnambulist monologues, to articulate the fears and obsessions of the war-torn world. Although such a great poet’s thoughts on a decisive moment of world history are invariably interesting, it’s the form of this poem that elevates it to a level few other twentieth-century writers ever achieved. Eschewing the modern conventions of free verse, and casting off rhyme as crude and unsophisticated, Auden chose to write this poem in alliterative tetrameters: the same metre as Beowulf. The effect of such a bold formal experiment is to tie his poem back to the earliest oral traditions in English, to give it a sense of mead-halls and pillaging; in turn, this suggests that humanity finally reached its potential with the atrocities of the Second World War.

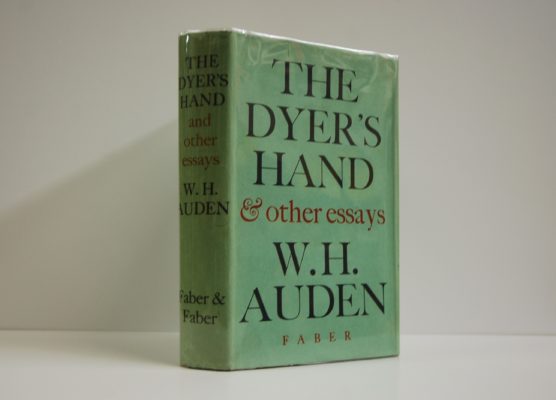

Other than The Dyer’s Hand—Auden’s masterly lectures delivered while teaching at Oxford—the highlight of our library remains The Shield of Achilles, which remains his best-selling book. Once again, Auden penetrates the American psyche with terrifying precision, examining the sweep of conformity and loss of individualism engendered by McCarthyism. Reworking a section of Homer’s Iliad, Auden depicts the goddess Thetis puzzling over the images adorning her son’s armour. Through Hephaestos’ divine, objective glimpse at humanity, Auden paints a barren world that lacks human compassion and empathy, instead only listening to a nameless voice who commands citizens. Throughout the poem, humanity is slowly dehumanised until it becomes ‘a million eyes, a million boots in line…waiting for a sign’. Auden’s picture is one of the starkest and most frightening portraits of totalitarianism in literature; and it is achieved with a poetic economy of which other writers can only dream.

If you’re interested in any of these items, please get in touch using this form or the telephone number and email address below.